Share the page

The obstacles to local production and access to treatment in Africa

Published on

Private Sector & Development #28 - Improving the quality and accessibility of african medicine

Providing access to quality medicines still poses a number of challenges in Africa. This 28th issue of Private Sector & Development magazine tackles attempts to come up with a few pointers and solutions for the future.

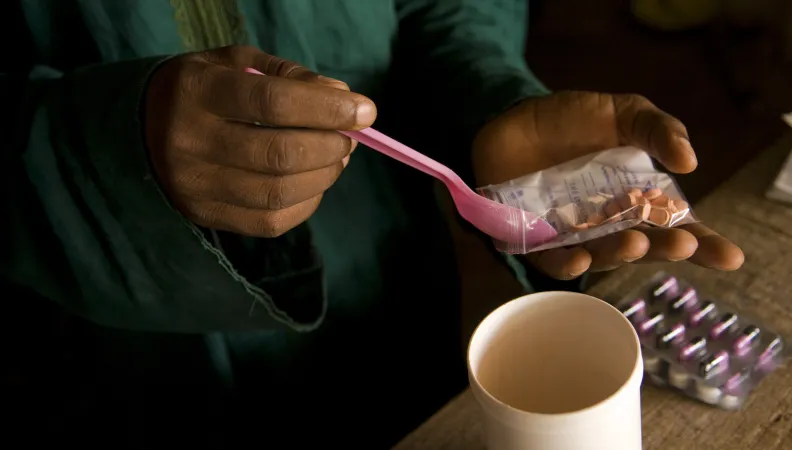

Access to proper medicine is a major challenge for African countries. While the global market is mature and highly profitable, the African Continent has been left far behind despite enormous needs and huge growth potential. Securing proper patient access to drugs and improving Africa’s integration into the global market for medicines means dealing with the challenges of product quality and availability as well as with financial accessibility.

Medicinal drug manufacturing is unequally distributed throughout the world. The African Continent only accounts for 3% of global output while 95% of the medicines consumed in Africa are imported. However, the situation differs widely from one country to another. South Africa and Morocco, the Continent’s veritable “pharmerging” nations1 manage to produce 70% to 80% of the drugs they need while certain central African countries need to import 99% of their medicinal requirements. And yet with estimated annual growth of around 10% between 2010 and 2020 – the second-fastest growing market after the Asia-Pacific region – Africa represents a dynamic proposition. Although it only contributes a small proportion of global pharmaceutical sales, over the past few years its massive growth potential has led the big pharma (i.e., pharmaceutical multinationals) and Asian generic drug manufacturers (see Insert) to start investing here2 alongside local producers. However, all players have to deal with a fragmented market due to specific national historical features.

The major players in the pharmaceuticals sector

Global pharmaceutical production is dominated by the big pharma, the major – generally Western – multinationals (Pfizer, Novartis, etc.). They are present across the entire value chain (from R&D to product manufacturing) and hold the key patents for innovative compounds. These big firms are followed by medium-sized groups specialised in a specific product category or therapeutic domain such as Boiron Group (homoeopathy) and Amgen (biotechnology-based drugs). The advent of biotechnology in the 1990s gave rise to start-ups specialised in R&D and this enabled the big pharma to outsource the most complex and risky phases of R&D. Lastly, the growth in generic drugs in both Northern and Southern countries has witnessed the emergence of global generic drug manufacturers like India-based Cipla and Ranbaxy and the Israeli firm Teva. The growing tendency to outsource certain stages of the production process has also been conducive to the emergence of new sector players. Manufacturers of active ingredients, located mainly in China, produce the chemical substance that possesses a therapeutic effect. Outsourcers located in developing countries produce medicines for third parties while contract research organisations perform certain activities on behalf of pharmaceutical firms (clinical testing or preparing applications for marketing authorizations, etc.).

Weakness of African output

South Africa, the Continent’s biggest producer, manufactures mainly for its own domestic market which is Africa’s biggest and was worth USD 3.19 billion in sales in 2016 3. The South-African Aspen Group, the fruit of a joint venture with GSK, is the Continent’s biggest drug manufacturer. Although not as big, Moroccan-based Cooper Pharma, is still leader in its market and is busy setting up production facilities in Côte d’Ivoire and Rwanda in order to crack the West and East African markets (Logendra, Rosen and Rickwood, 2013). Morocco is the Continent’s second-biggest producer with 40 production plants and 10% of output is exported. Aside from South Africa and Morocco, production facilities are currently in the pipeline in Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia, Ghana, Nigeria and Mozambique. More than 70% of Africa’s production is met by the 10 countries 4 that also account for two-thirds of its GDP. Most producers are small local firms. Local Northern and Southern African manufacturers produce both compounds under license and their own generic drugs, mainly for their domestic markets or those of adjacent countries but they do not have the resources to invest in R&D in order to tackle neglected diseases or even to keep local markets fully supplied. They suffer from a lack of competitiveness: local circumstances are not always conducive to deploying the Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs 5) required to do business at international level and to guarantee sufficient quality and continuous production. Moreover, fragmented pharmaceutical markets, due to the complexity and chaos inherent in different legal frameworks, hamper the competitiveness of local African laboratories vis-à-vis Asian manufacturers of generic drugs.

Health safety requirements and intellectual property rights are holding production back

Regulations concerning intellectual property rights (IPR, see Insert) have really hit local producers in developing countries hard and basically prohibit them from legally producing copies of drugs that have been patented in Northern countries for their own markets.

Intellectual property and medicines

Ever since the Agreement on Trade-Related aspects of Intellectual Property rights (TRIPS) signed at the WTO in 1994, medicinal drugs have been afforded global protection. These agreements fixed patent validity at 20 years (sometimes extended for another 5 years) and drew a distinction between patent-protected originator drugs, and unpatented generic drugs. However, under certain circumstances and subject to restrictive legal conditions, copies of patented drugs may be produced and distributed on a given local market under statutory or voluntary licensing arrangements. The declarations of Doha (2001) followed by Cancun (2003) provided for greater flexibility in this system. In particular, countries with statutory licenses were allowed to export part of their production to countries with insufficient or non-existent pharmaceutical production facilities. Despite this progress, certain African countries expressed reservations or requested clarifications. In January 2017, this process culminated in the adoption of a decisive amendment providing legal certainty that generic versions of patented drugs may be produced specifically for export under such arrangements (Abecassis and Coutinet, 2017).

Moreover – and this goes for all countries – new drug compounds require a marketing authorization that is only delivered following a series of very strict studies designed to test the drug's quality and safety. Drug manufacturers are subject to qualification procedures including compliance with GMPs. But few countries, particularly in Africa, have the reliable bodies that are needed to deliver such marketing authorizations and exercise any sort of effective control over the production of these products. This is why, in the specific case of priority diseases and at the request of certain procurement agencies, pre-qualification processes administered by the WHO have now been set up. However, because few African laboratories actually get this pre-qualification, international procurement agencies are turning to foreign competitors, especially those from India. Consequently, international investment – notably from the World Bank which is unable to find sufficiently viable prospects – remains pitifully small. To help African countries deal with this handicap, big pharma, the WHO and NGOs such as UNITAID are offering to provide technical assistance to local producers to help them comply with GMPs and obtain pre-qualification from the WHO. At the end of the day, all of these regulations (i.e., concerning IPR and health safety) have a huge influence on the accessibility of medicines.

The challenges of accessible treatment in Africa

Although global production of medicine is massive and diversified, it is frequently geared to rich and profitable Western markets and ill-adapted to African realities. There is very little R&D investment in infectious diseases that are endemic to African countries. Consequently, the Continent suffers from major shortages in upstream availability of drugs. So for example, according to OXFAM France, between 1999 and 2004, only three new innovative compounds targeting diseases prevalent in tropical countries were launched on the market out of a total of 163 new drugs.

For all medicines, even those produced in accordance with international standards, problems with distribution can undermine supply at local level. The poor state of transport infrastructure, unreliable electricity supply and insufficient control can affect key components of the distribution process such as the cold chain, storage conditions and compliance with “sell-by dates”. This is compounded by a highly fragmented distribution network: multiple distributors and wholesalers not only complicate distribution, they also push up prices (McCabe et alii, 2011). Such conditions are highly conducive to sub-standard and counterfeit medicines: in some African countries, counterfeit products represent half of all drugs on the market. Obviously questions of financial accessibility or “affordability” are tied to the price but aside from the price fixed by the producer, governments can improve accessibility by picking up some or all of the costs of certain drugs. They can do this either by using subsidies or a system of social protection. Governments can also leverage customs duties, taxes, import duties and conditions for obtaining licenses. However, such powers are frequently tempered by scarce resources and in some African countries, expenditure on medical drugs eats up as much as 30% of the health budget. Despite the major changes of the past few years, few countries have been able to set up a proper health and welfare system. Exceptional rates of public health insurance in Rwanda (91%) or Morocco (62%) mask the bigger picture: coverage is only 13.3% in Mauritania or a mere 3% in Burkina Faso (Del Hierro and Lambert, 2016). Consequently, in a lot of African countries, NGOs and bilateral aid play a big part in access to medicines. By analysing three criteria that influence the accessibility of medicines (availability, quality and affordability), we note that accessibility is a function of the combined actions of several types of actors: various ministries (Health, Trade, Finance, etc.), different structures in the medical drug supply chain (medical drug agencies, central procurement and distribution organisations, quality control agencies, certification bodies), different national and international financial backers, health centres (clinics and treatment centres, hospitals and biological laboratories), healthcare workers, patients’ associations and civil society organisations.

1 Combination of “pharma” and “emerging”.

2 From a growth perspective, South Africa, Nigeria, Ethiopia and Algeria are the most attractive markets.

3 The forecast rate of growth for 2016 and 2017 is 16.8%.

4 Algeria, Egypt, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Libya, Morocco, Nigeria, South Africa, Sudan and Tunisia.

5 As defined by the WHO, GMPs concern all aspects of manufacturing processes designed to “ensure that medicinal products are consistently produced and controlled to the quality standards appropriate to their intended use and as required by the product specification.” GMPs must ensure proper traceability of all stages in the production process.

References:

Logendra, R., Rosen, D. and Rickwood, S., 2013. Africa: A ripe opportunity: Understanding the pharmaceutical market opportunity and developing sustainable business models in Africa, White paper, IMS Health.

McCabe, A. Seiter, A. Diack, A.; Herbst, C. H.; Dutta, S. Saleh, K., 2011. Private sector pharmaceutical supply and distribution channels in Africa: a focus on Ghana, Malawi and Mali. Health, Nutrition and Population (HNP) discussion paper. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Del Hierro, E. and Lambert, A., 2016. « Quelle couverture du risque maladie en Afrique Subsaharienne », Secteur privé et développement (Proparco), n°25.

Abecassis, P. and Coutinet, N., 2017 (forthcoming). Économie du médicament, Paris, La Découverte, coll. Repères.