Share the page

The singular identity of a true "African child"

Published on

Kalaa Mpinga Founder Mwana Africa

Private Sector & Development #8 - The mining sector an opportunity for growth in africa

Often considered as being on the sidelines of globalization, Africa has during the 2000s benefited from continuously increasing investment and become a fully-fledged player as a result of the boom in the mining sector. Growth in demand for mineral resources coming from emerging countries has transformed Africa, which previously received little attention from the investment community, into an El Dorado for small and major mining companies in Europe, North America, and of course, China.

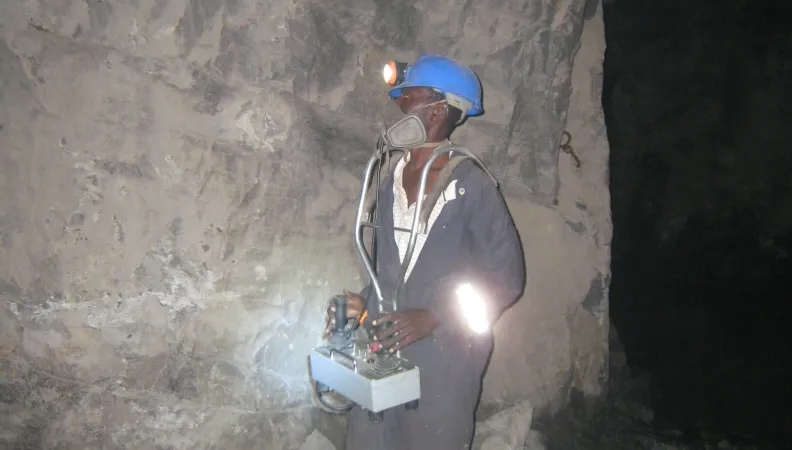

Mwana Africa – a mining company founded and managed by Africans – bases its development strategy on diversity (geographical sites, minerals exploited) and responsibility. Although employee safety is a priority, the company also mitigates the impact of the crisis on local populations. It pays for its employees' health care, provides them with accommodation and access to education. This responsible approach is extremely demanding on the company.

Mwana Africa means “African child” in several Bantu languages spoken in Eastern, Central and Southern Africa. It is also the name of the first mining group held by investors from Sub-Saharan Africa to be listed on the London Stock Exchange's Alternative Investment Market in October 2005. One of the unique features of the company lies in the structure of its team: former employees of Anglo American South Africa with undisputed expertise and an impressive number of contacts and a group of businessesmen from Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Kenya, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe, who have been successful on the continent. They all had a long-term vision whereby the development of the company would contribute to Africa's growth. Today, 20% of its capital is still held by African players; this African origin influences its investment strategy and the way in which Mwana conducts its operations on the continent. The company, whose market capitalization reached some USD 400 million prior to the financial crisis in the autumn of 2008 (USD 83.7 million at December 10, 2010), has a pan-African vocation with all its assets located exclusively in Africa: Angola, Botswana, DRC, Ghana, South Africa and Zimbabwe. As well as being one of the only junior mining companies to have such geographically diversified assets, Mwana's activity also focuses on several raw materials (gold, diamonds, nickel, base metals), while most companies operating in Africa focus on just one asset or one country.

A responsible approach, the key to long-term success

In addition, all operations are managed by Africans and follow a responsible process, which is considered to be one of the long-term keys to success. Indeed, the company seeks to offer its employees a safe working environment and look after their health; it also makes efforts to mitigate the environmental impact of its activities as much as possible. The company is aware of the fact that mineral exploitation carries a high risk that cannot be disregarded, and considers that it has the responsibility to create an environment which guarantees the safety of all its employees. Despite these efforts, a fatal accident unfortunately occurred at Mwana at the end of 2010. This is certainly little compared to its 2,982 staff – 322 office staff and 2,660 operators or engineers – , but it is, of course, obviously already too much. The reopening of the Freda Rebecca gold mine, located in Zimbabwe and owned by Mwana, which had been shut down during the period of hyperinflation in the country, provided an opportunity to make huge improvements in terms of safety, now a top priority. Similarly, this constant concern is a cornerstone of the new procedures defined by Bindura Nickel Corporation (BNC), Mwana's Zimbabwean subsidiary, for its reopening in 2011. BNC has consequently obtained the Occupation Health and Safety Assessment Series (OHSAS) 18001 certification,2 which is internationally recognized in the mining industry for health and safety at work. The main public health problems encountered in the regions where Mwana operates are either caused by malaria or are AIDS-related. In order to prevent and treat malaria, Mwana trains its employees and their relations and provides them with medication. Mwana Africa has set up anti- AIDS community programs in Freda Rebecca, Klipspringer (a diamond mine in South Africa) and BNC. These programs include awarenessraising campaigns, voluntary screening, health care and training for local communities. Freda Rebecca ensures employees infected with the virus and their dependents have access to antiretroviral (ARV) treatment. Mwana also takes concrete measures to mitigate the impacts its activities have on the environment. It makes an optimal use of resources, such as water, fuel and electricity. The management systems in place comply with the ISO 14001 standard3 (as early as in 2005 for BNC). This certification is also internationally recognized. Freda Rebecca implements a program established in compliance with the performance standards of the International Finance Corporation, World Bank and World Health Organization. As a general rule, Mwana recognizes its obligation to rehabilitate the sites where it operates and has made financial provisions for this, particularly in Zimbabwe and South Africa, in compliance with local laws.

Limiting the impact of difficult decisions

This responsible process was not affected by the unprecedented turbulence observed on global financial markets in 2008, which drastically reduced available financing and caused a slump in raw materials prices. For example, nickel prices fell from USD 55,000 a ton to under USD 10,000. Mwana had to resign itself to the fact that difficult decisions had to be taken. In November 2008, the decision was taken to shut down the BNC nickel mine, which at the time accounted for 100% of the Group's turnover, in order to conserve the liquidity of the Group and maintain all its operations. The fact that Zimbabwe was in a state of total decline – a victim of hyperinflation – made this decision even more difficult. There was obviously the risk that stopping BNC's activities for nearly three years would have a negative impact on the local population; indeed, it can be estimated that for each employee, ten members of the community benefit from the mine's activity. There was consequently the risk that laying off 2,425 employees would ultimately affect 30,000 people. To mitigate this impact, Mwana therefore decided to continue to pay for the accommodation, electricity and health care of BNC's employees during the closure. The company's African identity undoubtedly influenced its decisions in this context. Despite the unprecedented crisis in the mining sector over these last two years, Mwana's headcount has only been reduced by 8.6%, whereas the price of nickel saw a fivefold decrease over the same period. These difficult decisions have allowed Mwana to safeguard its future growth. The upturn in commodity prices and the improvement in Zimbabwe's economic situation with the end of the monetary chaos – following the abandonment of the national currency which was replaced by the US dollar – made it possible to resume operations in Freda Rebecca. A budget of USD 6.2 million was allocated to the first phase of works in 2009. A USD 10 million loan allocated in November 2009 by the Industrial Development Corporation of South Africa should allow a production of 50,000 ounces of gold as early as in 2011. It has been scheduled to resume BNC's operations in Zimbabwe this year.

Long-term development of local communities

The clout that the mining industry carries in certain African countries is unique. Its financing requirements – estimated at several billion dollars – and the investment potential it represents would allow it to make a sizeable contribution to the economic development of a country. When the crisis hit its peak, Mwana continued to make long-term investments, always with the concern of supporting the development of local communities, which are often located in remote regions. Indeed, it boosts the local economy by creating employment, helping SMEs to operate and develop, providing outlets for service activities and subcontractors located close to the mine (engineering, equipment maintenance, etc.) – not to mention its impact on the development of local infrastructure (roads, runways, telecommunications, etc.). For example, Mwana contributed to the installation of a mobile phone network in Ituri Province in northeastern DRC, which did not exist before its arrival. The impact of Mwana's activities consequently does actually go well beyond its direct contribution to employment. Mwana therefore takes part in the development of local communities; the company particularly considers that their education is partly its responsibility. For example, BNC provides all the resources required for t he primary education of its employees' children and has set up a fund (BNC Chairman's Fund) in order to facilitate access to secondary and university education. Each year, around ten scholarships are also allocated to higher education establishments that receive the deserving children of Mwana's employees. BNC consequently helps both the local university and the Zimbabwe School of Mines to operate. In Freda Rebecca, maternal, primary and secondary education is supported via school modernization. Finally, Mwana wishes to support redeployment for its employees (for those that request it) towards agriculture or craft industries, particularly by helping them gain access to microfinance. Finally, Mwana has anticipated measures aiming to give local populations economic autonomy, for example, by offering local investors a shareholding in the company. Today, the Chamber of Mines of Zimbabwe, of which BNC and Freda Rebecca are members, is negotiating with the government over the application of the law promoting the “indigenization” of Zimbabwean businesses. 47% of BNC, which is listed on the Harare Stock Exchange, is already held by Zimbabwean pension funds and investors. Moreover, Mwana has already announced the sale of 15% of Freda Rebecca to a local partner. It should be possible to promote and reinforce this method of firmly establishing companies at the local level in other contexts, in other African countries. It is certainly true that ever-increasing efforts are demanded of Mwana as a result of its African identity; but this demand is also an asset. By being transparent and responsible, Mwana Africa is both effective and recognized.

The limits of the model and how to improve it

The mining sector provides African States with revenues. Unfortunately, the exploitation of mineral resources is often at the expense of local populations and the environment, which makes its development difficult. There may be no doubt that mineral exploitation can benefit national economies, but the reforms introduced in the mining sector during the 1980s and 1990s under the auspices of the World Bank and IMF would not appear to guarantee this contribution. They are often criticized because of the considerable incentive measures that benefit mining companies. In addition, they have undoubtedly contributed to reducing the share received by African governments – a share they absolutely need to finance their social and economic development programs. The mining industry should promote the development of businesses in the countries where it is established, which provide it with a whole range of inputs. These businesses can build ties with other local economic sectors and consequently find outlets and speed up the development of techniques relating to mineral exploitation. The latter is by nature not sustainable, the lifespan of a mine is always limited as the resources end up being exhausted. However, thanks to the ties built with other economic sectors (upstream, downstream and via by-products), a mine can be guaranteed a certain level of sustainability. If their activities are to truly benefit local populations, mining companies must adopt a long-term vision, give priority to the development of sustainable mines and build mutually-beneficial partnerships with the States and peoples of the countries that host them. It is possible to create wealth for the continent and give Africans a greater share, provided the continent's mineral resources are exploited in an integrated manner – and if this is to be achieved, there must be consultation among all players.

Author(s)

Kalaa Mpinga

Founder

Mwana Africa