Share the page

The renewal of African banking sector

Published on

Paul Derreumaux CEO Banque africaine de développement

Private Sector & Development #16 - New players and new banking models for Africa

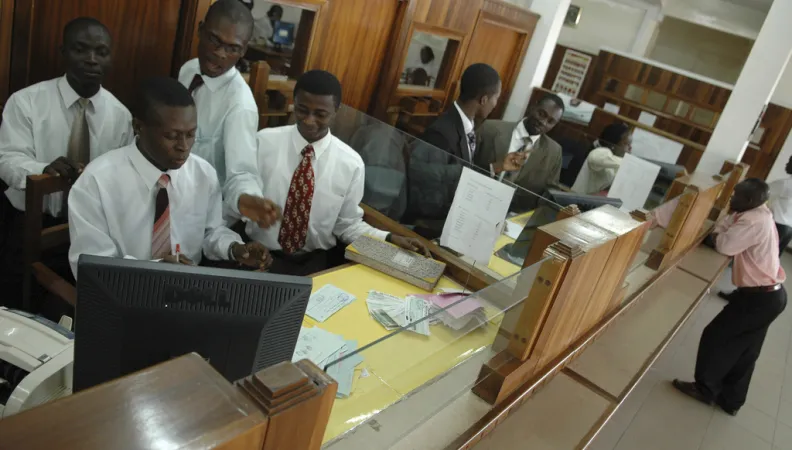

The African banking sector – largely dominated by the European banks through to the late 1990s – is currently undergoing radical change. Alongside the sector’s traditional players, regional operations are emerging – and steadily evolving into genuinely pan-African groups. These banks, whether they are local, regional or continental, are deploying a more aggressive growth strategy, seeking to penetrate new market segments and reach target groups previously excluded from the banking system. They are growing branch networks and introducing innovative, low-cost services better suited to underbanked populations.

Banking systems in Africa have undergone major changes in recent decades. The emergence of African groups and increased competition have forced the sector to adopt growth strategies based in particular on a more diversified customer base and product range. Despite its vitality, the sector faces new challenges to consolidate, to expand and to support the continent's development.

In 2012, Africa's 200 largest banks had total assets of approximately USD 1,110 billion and a net banking income (NBI) of USD 45 billion. The dominant countries were South Africa, Nigeria and North Africa, with shares of 36%, 9% and 40% in assets and 45%, 15% and 32% in NBI respectively. The banking sector in sub-Saharan Africa is nevertheless still extremely diverse, particularly in terms of banking concentration and the banking penetration rate, which ranges from more than 50% in South Africa to less than 10% in Francophone Africa. Today commercial banks continue to dominate the financial systems of sub-Saharan Africa. After countries in the region gained independence, the sector was essentially composed of state-owned banks and a few major banks of the former colonial powers. Over the past forty years, major changes have gradually overhauled Africa's financial systems. The first private African banks appeared and set up regional networks; meanwhile, the sector was suffering from the withdrawal of large foreign corporations and the difficulties faced by state-owned banks. The creation of regional markets fostered the emergence of regional and in some cases continental African banking groups. These different phases and constant changes have shaped Africa's present financial systems – along with their strengths and weaknesses.

Positive changes in the banking sector

Overall, Africa's banking sector is now regarded as robust. The widespread liquidity and solvency crises of the 1970s and 1980s in Benin, Cameroon and Madagascar, for example, which had impacted commercial banks and their supervisory bodies, are now gone. Practices improved and structural changes were made, such as the creation of regional banking commissions in francophone Africa and improved supervision of counterparty risk at most commercial banks. Today's banking institutions demonstrate greater resilience and higher professional standards – and are therefore posting better results. Spurred on by accelerating economic growth, to which they are contributing, banks are seeing steady improvement in their performance and operating indicators. The annual ranking of the 200 largest African banks highlights these positive changes. Clearly the situation varies considerably from one country to another, depending on the country's economy, environment and financial services regulations. Yet progress is undisputed and noteworthy, regardless of geographical region, country or bank. The shape of banking systems reflects the overall improved health of sub-Saharan Africa, while being consistent with the intrinsic characteristics of the continent's different economic spaces. Within this spectrum, South Africa remains a world apart. Its four main banks are each three to four times more powerful than those below them in the African bank rankings. These four banks alone account for more than 35% of the total assets of Africa's top 100 banks (Figure 1).

Despite this substantial lead – which is narrowing only slowly – South African banks do not have a network on the continent consistent with their size, no doubt due in part to the growth potential in their domestic market and foreign investment restrictions. But South Africa will of necessity have a key role to play in the evolution of African banking systems, as seen in some recent trends: Nedbank has increased its stake in Ecobank, while Barclays and Absa have restructured and merged operations into Barclays Africa Group, and Stanbic has arrived in Nigeria.

Fierce competition and stricter regulations

Foreign bank subsidiaries have gradually lost their dominant position – probably permanently – to African banks. The new leaders, which are few in number, come from several countries. Morocco and Nigeria have the most extensive networks, followed by South Africa and, more recently, Kenya and Gabon. Yet it is an unstable equilibrium, because all of these leaders are powerful and enterprising, particularly because of the size they have reached in their home countries. And all are driven by the same ambition: to expand as much as possible by leveraging their capital resources and know-how. New markets are now being sought throughout sub-Saharan Africa; banks are expanding either by acquiring an existing bank or by creating a new entity, depending on circumstances. Today, the only impediments to this geographical expansion are the financial limitations of some networks or practical difficulties in identifying attractive targets. Rarer still are networks operating across the entire continent, i.e. in at least two linguistic regions, such as Ecobank, Bank of Africa and United Bank for Africa (Table 1).

These are likely soon to be joined by several others. With no boundaries to its sphere of action, the banking sector is undoubtedly leading the way and acting as a model; large African companies, which have always thought in regional terms, will thus have to follow suit and go beyond their geographical boundaries, which have become too restrictive. As is often the case, the private sector is providing a model for integration, with banks acting as a crucial catalyst, particularly through the support they offer to their customers. In this competitive environment, commercial banks are developing similar strategies to attract new customers and diversify their operations. Banks are relying on their branch networks, which are expanding quickly, and as a result banking services' penetration in Africa is increasing. Products and services are multiplying and becoming more innovative based on e-payment, Internet and mobile banking technologies. Commercial banks have the same targets – from individuals to large businesses – as they seek to capture a share of markets that are still narrow and in which players have to work with all types of customers. Today African banks are better organised and more innovative, and are catching up with and even getting ahead of their Northern counterparts when it comes to mobile banking and prepaid credit cards.

Initiatives taken by central banks are another key factor in the sector's evolution, starting with the establishment of independent supervisory authorities using rules based on international banking standards. These bodies were set up in the English-speaking countries of East Africa in the 1970s and in francophone Africa at the end of the 1980s. The massive increase in the minimum capital requirement is a further illustration of these evolutions: Nigeria's sudden requirement in 2005 to set the minimum regulatory capital at USD 200 million reduced the number of banks by 75% within a few years and forced survivors to go beyond their national borders in an attempt to get a return on their new capital. The extent and pace of reforms in francophone Africa are very different; control procedures are often lax and inadequately monitored. Be that as it may, increasingly strict compliance with the rules of international banking supervision is the final step in the sector's overhaul: the Basel II standards, international financial reporting standards (IFRS) and new prudential ratios are being applied slowly but surely throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Francophone Africa has been late to adapt.

Addressing new challenges

As a result of all these changes, African banking systems have improved significantly over the past two decades, and customers have been the first to benefit. This is particularly true for private customers, who are now being offered products better suited to, and even boosting, their needs – educational loans, ‘pilgrimage' loans, retirement savings, and savings accounts tailored for young people, all of which are available at an increasing number of branches. Large, well-organised companies are also benefiting, thanks to the now common practice of syndicating among subsidiaries of the same banking group, or among banks in the same region. Also benefiting are the relationships between banks and microfinance organisations, which are multiplying and diversifying as their operations increasingly converge.

Yet despite this, weaknesses remain. Small and medium enterprise (SME) financing remains an issue, even though the most aggressive retail banks today sometimes allocate more than 25% of their direct loan portfolio to this segment. Substantial effort still needs to be made, and it must be supported, sustained and jointly led (Derreumaux, P. 2009). Banks must achieve higher professional standards and be more innovative with risk analysis, guarantees and financing arrangements, while companies need to increase their equity capital and become more organised and transparent in managing their financial flows. Mortgage loans, which have long been the subject of defaults, seem to be benefiting from the recent but rapid involvement of a growing number of banks and from more advantageous refinancing terms for loans granted by institutions. This progress should eventually lead to growth in the supply of quality housing suited to the purchasing power of the population – which would have a ripple effect throughout the sector. By contrast, ‘bancassurance', which was introduced almost a decade ago, has barely taken off, even though the insurance sector is undergoing a massive overhaul, much like that experienced by the banking sector.

The story does not end here; most of the current changes are expected to continue, leading to ever more focused and efficient banking systems. But the African financial system needs additional improvements if it is to continue to drive Africa's economic growth. Some are government-dependent; by supporting the banks, governments can pursue their own goals, such as improving the legal system and using tax incentives to obtain, quite fairly, lower credit costs. Yet most of the required improvements depend on the ability of the banks themselves to meet new challenges. Optimal use must be made of new technologies, and more effective procedures need to be implemented to increase staff productivity. Banks must prevent fraud, improve product penetration, capture a substantial number of customers with little or no banking experience, and attract more savers. Lastly, it would be useful if bulk financing at retail banks was facilitated. Dematerialised payment systems are also a major contributor to these developments: mobile banking has already started to ‘move the goal posts', as telecommunications companies, which are at the cutting edge of these vehicles, start to emerge as potential rivals. Meanwhile, other systems that rely increasingly on electronic banking are being developed. The winners will be those who can develop and deliver tools that combine simplicity and security and are appropriately tailored to their environment. The emergence of securities markets, corporate venture capital and guarantee funds must also be fostered so that companies have access to a full range of tools that can help them expand. Because of their central position, banks can play a major role in these improvements – if they dare to do so and if they are encouraged by governments.

Convergence may well be the watchword of these desired changes: convergence of mechanisms with those implemented by other sectors; convergence of banks with other possible financial sector players; convergence of bank and insurance players, who together could examine potential joint action. And other changes are afoot, such as the opening up of countries still off-limits to foreign banks, and the arrival of major new players in the African banking system. In this regard, the large European banks seem to be returning with measured steps, while Chinese and Indian institutions seem to be in no rush. The surprise could come from the Middle East, which understands the challenge and promises that the African continent represents, and appears poised to act quickly.

RÉFÉRENCES:

Derreumaux, P. 2009. The difficulties SMEs face to access finance in Africa: whose is to blame? Private Sector & Development magazine, May 2009.

Jeune Afrique, 2012. Hors série spécial finance, Edition 2012